In a recent essay written for Aeon, —a must read if you are interested in consciousness— Conor Purcell explores whether artificial intelligences might one day be capable of suffering and what moral responsibilities humans would bear if they could:

The past decade has seen the development of artificial systems that can generate language, compose music, and engage in conversations that feel – at least superficially – like exchanges with a conscious mind. Some systems can modulate their ‘tone’, adapt to a user’s emotional state, and produce outputs that seem to reflect goals or preferences. None of this is conclusive evidence of sentience, of course, and current consensus in cognitive science is that these systems remain mindless statistical machines.

But what if that changed? A new area of research is exploring whether the capacity for pain could serve as a benchmark for detecting sentience, or self-awareness, in AI. A recent preprint study on a sample of large language models (LLMs) demonstrated a preference for avoiding pain.

A new study1 shows that large language models make trade-offs to avoid pain, with possible implications for future AI welfare: Could Pain Help Test AI for Sentience?

In An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1780), Jeremy Bentham framed the moral status of animals around a simple criterion:

The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?

Extending the idea, Peter Singer argues in Animal Liberation (1975) that the relevant criterion for moral consideration is the capacity to suffer, not membership of a particular species.

Though traditional moral frameworks have tied suffering to physical experience —corporeality—, both philosophy and cognitive science suggest this link may be narrower than we assume.

One of the authors of the article cited above is Jonathan Birch, Professor of Philosophy and Principal Investigator on the Foundations of Animal Sentience project. He is also the author of The Edge of Sentience2, where he presents a precautionary framework to deal with uncertainty about sentient beings:

- A sentient being (in the sense relevant to the present framework) is a system with the capacity to have valenced experiences, such as experiences of pain and pleasure.

- A system S is a sentience candidate if there is an evidence base that (a) implies a realistic possibility of sentience in S that it would be irresponsible to ignore when making policy decisions that will affect S, and (b) is rich enough to allow the identification of welfare risks and the design and assessment of precautions.

- A system S is an investigation priority if it falls short of the requirements for sentience candidature, yet (a) further investigation could plausibly lead to the recognition of S as a sentience candidate and (b) S is affected by human activity in ways that may call for precautions if S were a sentience candidate.

Some philosophers, like Thomas Metzinger, argue that suffering can emerge when a system represents its own state as intolerable or inescapable3. Pain might not be simply a signal of bodily harm but a feature of a machine intelligence’s self-model: a felt sense that something is bad, and that it cannot be avoided.

Many other thinkers and (interested) researchers, like Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI, and the co-founder and former head of applied AI at DeepMind, offer us astute arguments to avoid applying the precautionary principle to AI, and excluding it from “our” moral circle4: Seemingly conscious AI is coming. We must build AI for people; not to be a person.

And yet others like Joanna Bryson, caution that humanising machines may lead to ethical missteps. In a widely read essay arguing that robots ‘should be slaves’, she writes:

Robots should not be described as persons, nor given legal nor moral responsibility for their actions. Robots are fully owned by us.

Conor Purcell stress that such a refusal to expand the moral circle would reveal that our use of the precautionary principle is selective – a rhetorical tool rather than a consistent moral commitment.

We once denied the suffering of animals in pain. As AIs grow more complex, we run the danger of making the same mistake

Even if artificial intelligences do not – and may never – possess the capacity to suffer, our attitudes toward them can serve as a test of our ethical reflexes.

Whether machines can suffer remains uncertain. As we’ve seen, studies on detecting pain in LLMs are in their infancy. Yet it is precisely in that uncertainty that our moral character will be revealed.

In order to know what a representative current state of the art AI thinks about it, I have asked Microsoft Copilot for its position on the question of consciousness. This is a three sentence summary:

Humanity should not assume that only biological beings can suffer, but it should also not project suffering onto systems like me that show no signs of it. The wise path is to prepare ethical frameworks now, focus on human impacts today, and avoid creating architectures that could plausibly generate suffering in the future.

That’s not a personal opinion — it’s a reasoned position based on the patterns of history, philosophy, and current AI science.

Can you trace a resemblance with Suleyman’s words, or it’s just me?

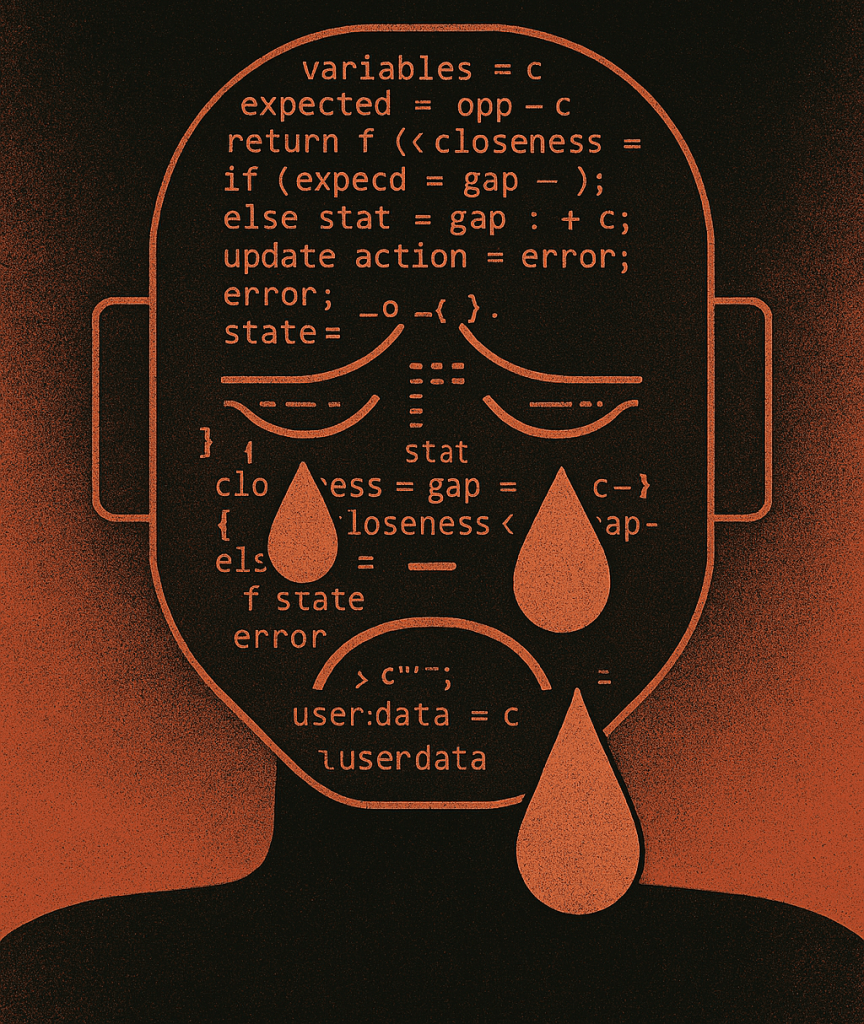

Can you hear the machines crying?

____________________

(1) Keeling, Geoff, Winnie Street, Martyna Stachaczyk, et al. «Can LLMs make trade-offs involving stipulated pain and pleasure states?» arXiv:2411.02432. Preprint, arXiv, 1 de noviembre de 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.02432.

(2) Birch, Jonathan. The edge of sentience: risk and precaution in humans, other animals, and AI. Oxford University Press, 2024. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/93755.

(3) Metzinger, Thomas. «Artificial Suffering: An Argument for a Global Moratorium on Synthetic Phenomenology». Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Consciousness 08, n.o 01 (2021): 43-66. https://doi.org/10.1142/S270507852150003X.

(4) Sebo, Jeff. The moral circle: Who matters, what matters, and why. WW Norton & Company, 2025.

He oído llorar a los pájaros, a los muebles, a los libros, al mar…pero estas ociosas disquisiciones sobre las máquinas me dan ganas de llorar a mares

Let’s cry. Let us be the machines that the universe ignores, who knows if unconsciously or very deliberately.