A higher frequency of potentially disruptive, critical events and phenomena, both in the external environment and society, reminds us of the need to reimagine foresight practice. Current visions of transition are usually anchored in an incremental paradigm that excludes radical change. Scenario planning have been criticized for being unimaginative, not too dissimilar to the present. The richness of imagination of science fiction artifacts offers plenty of opportunities to extend horizons1.

Science fiction describes less a literary genre with more or less clearly demarcated boundaries and more a way of thinking and perceiving, a toolbox of methods for conceptualizing, intervening in, and living through rapid and widespread sociotechnical change

Traditionally neglected if not despised by researchers in the humanities and social sciences, science fiction is changing status2.

Anthropologists, historians, sociologists, and political scientists are not only more and more often appealing to science fiction as a conceptual tool for their investigations, but sometimes even go so far as to break the rules of academic writing by publishing texts that adopt explicitly science-fictional strategies, that is, counterfactual, told in the future tense or from impossible points of view

Let’s briefly explore three examples in recent studies using these two complementary ideas:

The “six” scenario archetypes framework

In a paper3 published in Future in 2020, Alessandro Fergnani & Zhaoli Song propose a new scenario archetypes framework generated by extracting archetypal images of the future from a sample of 140 science fiction films set in the future, starting with Metropolis (1927) and ending with Wondering Earth (2019).

Their rationale is that the well-established Jim Dator’s Four Generic Scenario Archetypes method is not immune to the often-raised criticisms of scenario planning. The idea behind Dator’s model is that the four archetypes can parsimoniously explain the vast variations of human imagination about the future. Dator reached his conclusion after having perused public plans, politicians’ statements, books and essays about the future, science fiction novels, films, and opinion polls. In more than one occasion.

Dator contended that these archetypes were not “made up” or invented, but rather the result of years of empirical research (…) However, Dator never reported having tested this claim empirically.

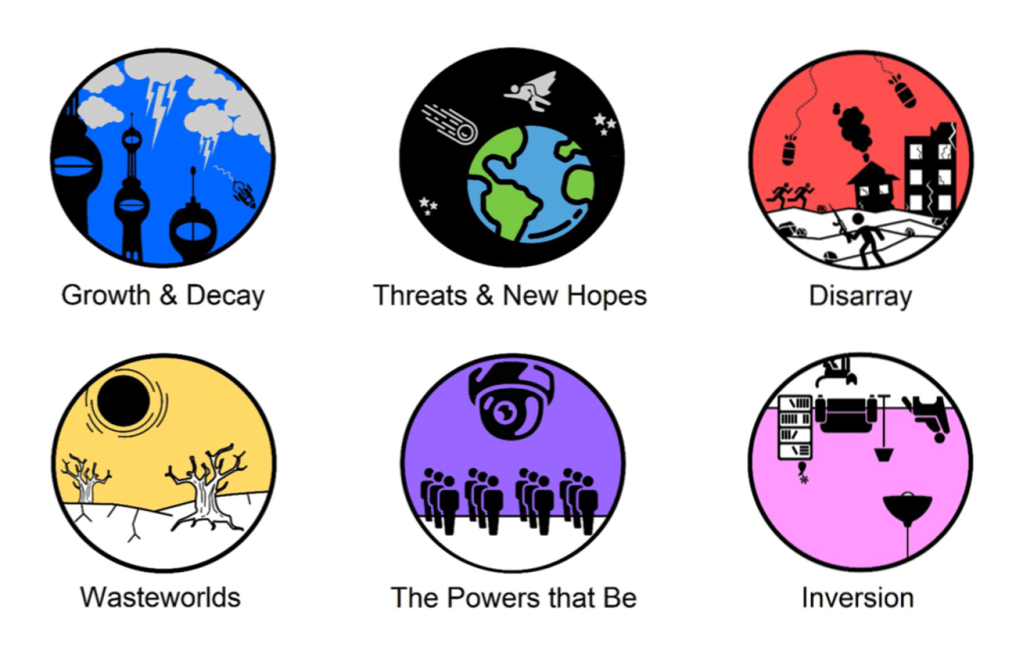

Fergnani & Song identify Six main archetypes from the fiction films which they name Growth & Decay, Threats & New Hopes, Waste worlds, The Powers that Be, Disarray, and Inversion.

Growth and Decay: This archetype involves the continuation of the current capitalistic status quo, which grows even more rampantly. Corporations reigns unalloyed, potentially extending their power to policing, urban security, the management of public infrastructures, and law enforcement. Governmental power is absent or sidelined. Current technologies also grow steadily, pushed by monetary gains and controlled by corporations. Hints of societal collapse or decay are found in the society.

This archetype is represented mainly by the cyberpunk genre in cinema. Notable examples include Metropolis, Blade Runner, Avatar and Ready Player One.

Threats & New Hopes: No significant change affects mankind, and human life conditions are very similar to the present. However, an imminent catastrophic or apocalyptic event or phenomenon threats mankind’s existence. This impending occurrence can take various forms, including environmental disasters, man-made destructions, or aliens’ invasion. National and supranational governmental bodies or military organizations collaborate to devise a global plan of rescue, while the private sector is less relevant.

This archetype is represented by the disaster genre in cinema. Notable examples in cinema include 2012, Pacific Rim, Transcendence, Interstellar, Downsizing, and Wondering Earth.

Wasteworlds: A catastrophic event or phenomenon has already occurred, bringing about substantial transformations on a global scale. The atmospheric environment is often perniciously hit, forcing humans to adapt to drastic life conditions.

This archetype is represented by the post-apocalyptic genre in cinema. Notable examples in cinema include Mad Max, Waterworld, The Postman, and WALL-E.

The Powers that Be. A catastrophic event or phenomenon, often man-made, has already occurred. Although this has left a scar on the human species to the point that population is often significantly reduced, mankind resumes its path to progress quickly thereafter. However, strict totalitarian or dictatorial powers emerge from this checkered past, ostensibly to carefully prevent the occurrence of other man-made devastating events or phenomena in the future. Technology is advanced, but centralized in the hands of governmental bodies and used as an instrument of control.

This archetype is represented by the dystopia genre in cinema. Notable examples include Aeon Flux, Hunger Games, Divergent, The Giver, and The Maze Runner.

Disarray: In absence of apparent transformational changes in the economy or atmospheric environment, mankind faces structural endogenous problems. The globe is plagued by any of the following: endemic crime, social unrest and disorder, widespread poverty, ignorance, infertility, violent confrontation and war, famines, or pandemics; or by a combination of these. Although the private sector is still present, military and policing organizations, either official or non-official, have a more central role in this future. Individual endeavours zero in on restoring or maintaining justice, order, or protection of citizens.

This archetype is also represented by the dystopia genre in cinema. Notable examples include Idiocracy, Dredd, and Children of Men

Inversion: The role of mankind is turned upside down, as it is outpaced or subjugated by a superior civilization, agent, or organism. Human beings no longer dominate the planet. Often times, they are instead dominated by creatures of higher physical prowess, of which they become preys. Alien species invading the planet or the entire galaxy is an example. However, this superior entity could also manifest itself in more subtle manners, such as an ostensible creator or supervisor with whom mankind ought not interfere.

This archetype is represented by the aliens’ genre in cinema. Notable examples in cinema include A Quiet Place, After Earth, Planet of the ApeS, and Alien: Covenant

As for the differences with the dominant Dator’s framework:

- Growth & Decay is more nuanced, and, authors believe, more tied to the reality of the status quo than Continued Growth.

- A relatively more extreme Collapse archetype, representing the aftermath of a transformational event or phenomenon that pushes civilization to its limits. The collapsing process in the making allows greater sophistication of futures thinking

- The six archetypes are all transformational in nature, albeit in different ways, in contrast with only one archetype in Dator’s framework: Transformation.

Rethinking the relation between human and nature

Accumulation of environmental data confirms that Earth’s ecosystems are experiencing dramatic changes. Current visions of transition are anchored in an incremental paradigm that excludes radical change. Using science fiction literature and cinema, this article aims to build such drastic change hypotheses and explore the political–ecological features of future societies emerging from a rupture phenomenon.

A paper4 by Corinne Gendron and René Audet, published this year, introduces six such hypotheses called Scenarios that were induced from the systematic study of a body of work in classical science fiction production.

Science fiction appears indeed as the most natural corpus to exercise the hermeneutics of invention. For the purposes of this paper, science fiction is understood as defined by Davenport (1955, p. 15), who stated that “Science fiction is fiction based upon some imagined development of science, or upon the extrapolation of a tendency in society,” or by Gunn (1977), who defined it as “the branch of literature that deals with the effects of change on people in the real world as it can be projected into the past, the future, or to distant places. It often concerns itself with scientific or technological change, and it usually involves matters whose importance is greater than the individual or the community.”

The fouled nature: The downward spiral of human–nature relationship Pollution, atomic war, and other anthropogenic destructions have made planet Earth quasi-inhabitable. Nature—or what’s left of it—is contaminated or scarce. This is the starting point of the fouled nature scenario. In this scenario, the complete disappearance of nature provokes the dissolution of humanity.

The classic Mad Max series is a good case study. Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) exemplifies this post-apocalyptic future.

Pockets of society in inhospitable nature: Many science fiction novels and movies develop the idea of an inhospitable nature that leads human societies to leave Earth or to concentrate in shrunken spaces where cohabitation faces the challenge of finding new norms of common living.

In Robert Silverberg’s The World Inside (1971), the Earth’s population reaches 75 billion. Concentration of huge populations in small, civilized pockets can be found in Jean-Christophe Rufin’s Globalia (2004) or John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar (1968).

Artificial paradises and the substitutes to nature The catastrophist view of future destruction of nature is also the starting point of the artificial substitute to nature scenario. The climate crisis (in Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, 1965), consumption society (in Frank Herbert’s The Santaroga Barrier, 1978), and overpopulation (in Soylent Green, 1973), for example, would lead human societies to develop artificial universes through the use of drugs or other technologies that allow for a happier living in spite of the state of crisis.

Substitutes to nature could also materialize in artificial worlds such as video games (Ready Player One) or reality TV (The Truman Show).

The mastered nature: Between geoengineering and bioengineering: Terraformation, geoengineering, and bioengineering are common topics of science fiction literature. The mastered nature scenario exposes this perspective and often places it in the ethical debate on biocentrism and anthropocentrism that is at the core of environmental philosophy.

In the second Star Trek movie, The Wrath of Khan (1982), a mysterious seeding technology is supposed to produce a new earth-like paradise in a matter of days. Geoengineering is more in phase with actual Earth system science. It is the context of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars (1992). In Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl (2009) the loss of nature is the consequence of too much control over it.

The cybernature (Intelligence as an emerging propriety of human networks): Intelligence in the cybernature scenario is a natural phenomenon (as a difference with AI). This scenario is more recent and closely linked with the rise and diffusion of complex system theory in natural sciences. In short, complex system theory affirms that systems can produce “emerging properties” at higher levels, which cannot be understood only through lower level systems.

Programs, viruses, and other software acquire the capacity to adapt, to change, to reason, to communicate, and to reproduce. It eventually imposes itself to the human species as a new—natural and cybernetic—form of life.

Three interwoven patterns are seen as possible outcomes:

- Cyber totalitarians and total war between the organic and the cybernetic. Battlestar Galactica series (2004).

- The weakness of the cyber beings. Dan Simmons’ Hyperion and Endymion saga (1989-1997) is a case of a parasitical relation that comes to evolve in the direction of cyber domination.

- Cyber beings compared with infantile or juvenile humans, often in search for individual identity. Jane in Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game series (1985-1996).

Nature as intelligent design: It is not so rare that science fiction pictures harmonious human–nature relationship, in which a caring nature is attributed a spiritual dimension. It is the case with A. E. van Vogt’s classic The World of Null-A (1948), with Asimov’s Foundation and Earth (1986), and, in a very explicit manner, with James Cameron’s Avatar (2009).

Speculative futures for higher education

A paper by Sian Bayne and Jen Ross, also published this year, uses speculative methods as a way of imagining futures for higher education in open, non-predictive ways.

The paper presents a series of speculative scenarios and microfictions focusing on worlds ruptured by climate change, artificial intelligence, revolution and the technological enhancement of humans, connecting each of these to current critical research focused on climate crisis, ‘big tech’, rising global injustice and ‘big pharma’. It emphasises the vital contribution and place of higher education within such futures, and advocates for speculative methods as an approach to maintaining hope.

The speculative scenarios were written in 2022 as prompts for discussion about higher education and its possible futures. The first four scenarios are described in the paper. More information can be found in the Centre for Research in Digital Education: Higher Education Futures.

As an antidote to predictive, closed forms of future-making, speculative scenario-building and storytelling – as used in this paper – can function as ‘a medium to aid imaginative thought…

Speculative methods can provide a way to scrutinise and contest dominant imaginaries, and create new, perhaps preferable ones. They should help open up new kinds of conversation capable of supporting active and fundamental hope.

Extinction-era universities: Climate disaster is well underway with catastrophic weather events and mass movement of people. Universities lead the global response through delivery of mass public survival education.

AI academy: Surveillance is pervasive. Behavioural data is constantly harvested by AIs and delivered to administrators with infinite granularity. AIs provide instant categorisation of students’ capacities through analysis of their personal data.

Justice-driven innovation: Unrest prompts radical political change. Transdisciplinary research focusing on specific social challenge areas is prioritised. Globally-accessible, open learning is woven through local, autonomous ecoversities.

Enhanced enhancement: Routine cognitive enhancement is now normal. Almost all students and staff use smart drugs and electronic neuro-stimulation, as cultures of performance, productivity and metricisation intensify in universities.

The universal university: Attendance at campus-based universities has ended – the student body is online. Advances in virtual reality enable dynamic community-building as if you were there. Everyone can participate as new routes to access are mandated by governments across all continents.

Extreme unbundling: Teaching is sold directly to individuals by academics selling their expertise freelance. People learn through life, accumulating credit validated through performance analytics. Academics are loosely affiliated to industry-funded research collectives of varying prestige and no physical location.

Return to the ivory tower: Widening participation policies have failed as automation decimates semi-skilled work. In-depth academic study is now only for a small number likely to move into ‘elite’ roles. The gated physical campus is once again the locus of university life.

The university of ennui: Automation has taken all the jobs. Paid work has ceased to be the defining activity of adult humans. Everyone now has time for lifelong higher education. However humans are struggling to understand what they are for.

…

Are you still thirsty for futures scenarios in science fiction? You can find more here, on military planning…

____________________

(1) Vint, Sherryl. Science Fiction. Mit Press, 2021.

(2) Mengozzi, Chiara, and Julien Wacquez. ‘On the Uses of Science Fiction in Environmental Humanities and Social Sciences: Meaning and Reading Effects’. Science Fiction Studies 50, no. 2 (2023): 145–74. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/347/article/900278/summary.

(3) Fergnani, Alessandro, and Zhaoli Song. ‘The Six Scenario Archetypes Framework: A Systematic Investigation of Science Fiction Films Set in the Future’. Futures 124 (2020): 102645.

(4) Gendron, Corinne, and René Audet. ‘Rethinking the Relation between Human and Nature: Insights from Science Fiction’. Business and Society Review n/a, no. n/a. Accessed 30 July 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/basr.12362

(5) Bayne, Sian, and Jen Ross. ‘Speculative Futures for Higher Education’. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 21, no. 1 (17 June 2024): 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00469-y.