Short answer: No. Very likely, you won’t.

Over the course of the twentieth century, human life expectancy at birth rose in high-income nations by approximately 30 years, largely driven by advances in public health and medicine.

In 1990, it was hypothesized that humanity was approaching an upper limit to life expectancy (the limited lifespan hypothesis). A new study1 published in Nature Aging suggests that there is no evidence to support the suggestion that most newborns today will live to age 100.

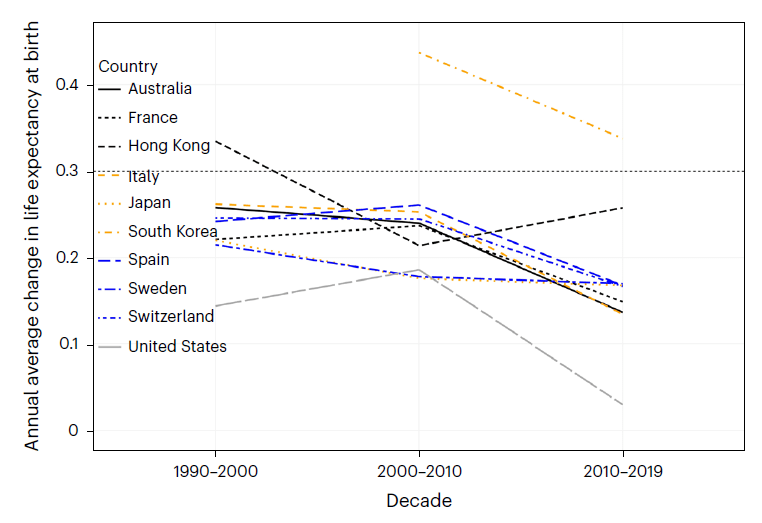

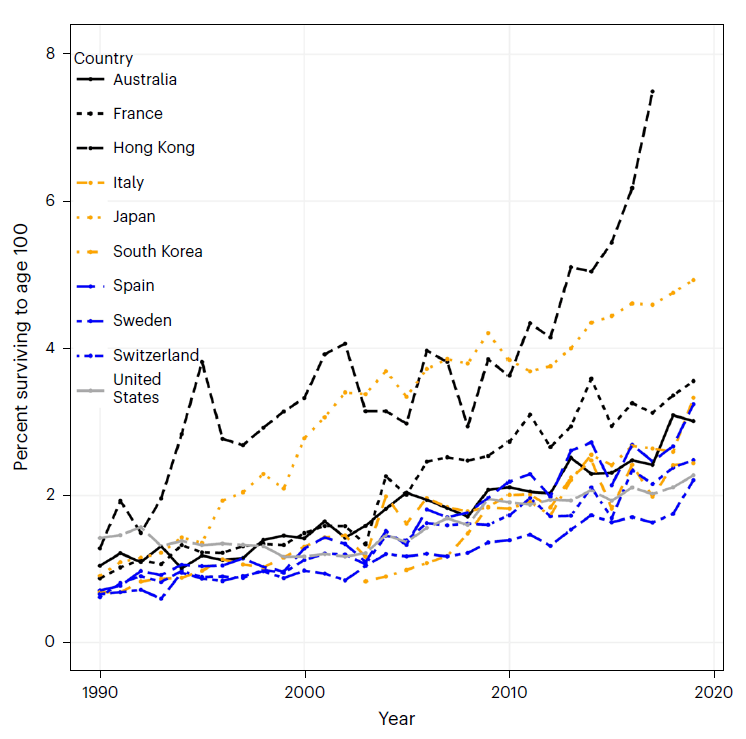

Over the course of the twentieth century, human life expectancy at birth rose in high-income nations by approximately 30 years, largely driven by advances in public health and medicine. Mortality reduction was observed initially at an early age and continued into middle and older ages. However, it was unclear whether this phenomenon and the resulting accelerated rise in life expectancy would continue into the twenty-first century. Here using demographic survivorship metrics from national vital statistics in the eight countries with the longest-lived populations (Australia, France, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) and in Hong Kong and the United States from 1990 to 2019, we explored recent trends in death rates and life expectancy. We found that, since 1990, improvements overall in life expectancy have decelerated. Our analysis also revealed that resistance to improvements in life expectancy increased while lifespan inequality declined and mortality compression occurred. Our analysis suggests that survival to age 100 years is unlikely to exceed 15% for females and 5% for males, altogether suggesting that, unless the processes of biological aging can be markedly slowed, radical human life extension is implausible in this century.

____________________

Olshansky, S. Jay, Bradley J. Willcox, Lloyd Demetrius, and Hiram Beltrán-Sánchez. ‘Implausibility of Radical Life Extension in Humans in the Twenty-First Century’. Nature Aging 4, no. 11 (November 2024): 1635–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00702-3.

(Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.)

I do not think I’d like to 😉

I do not think I’d like to!