Prediction markets are forums for trading contracts that yield payments based on the outcome of uncertain events. There is mounting evidence that such markets can help to produce forecasts of event outcomes with a lower prediction error than conventional forecasting methods.

This is the beginning of a brief paper published in Science in 2008 by 22 prominent economists, 5 of them (as of today) winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, with more than 500 cites (according to Google Scholar).

The idea of prediction markets is not new1. Betting on future events has been a common practice in sports and horse racing, for example. On Wall Street, it was possible to bet on the outcome of American elections as early as 1868.

In a famous article published in 1945, The Use of Knowledge in Society, Friedrich Hayek showed that, as a by-product of their core activity of exchanging goods and services, markets become a mechanism capable of collecting vast amounts of private information and aggregating it to produce information useful to society as a whole.

For someone interested in the technology, innovation, the future (and investments) the idea of an information market is a poster child. Personally I’ve been waiting for (and preaching about) their possibilities and potential arrival for years, since I first entered into contact with the idea through (inhouse) experiences in Hewlett Packard and Google, and public experimental initiatives like the Iowa Market.

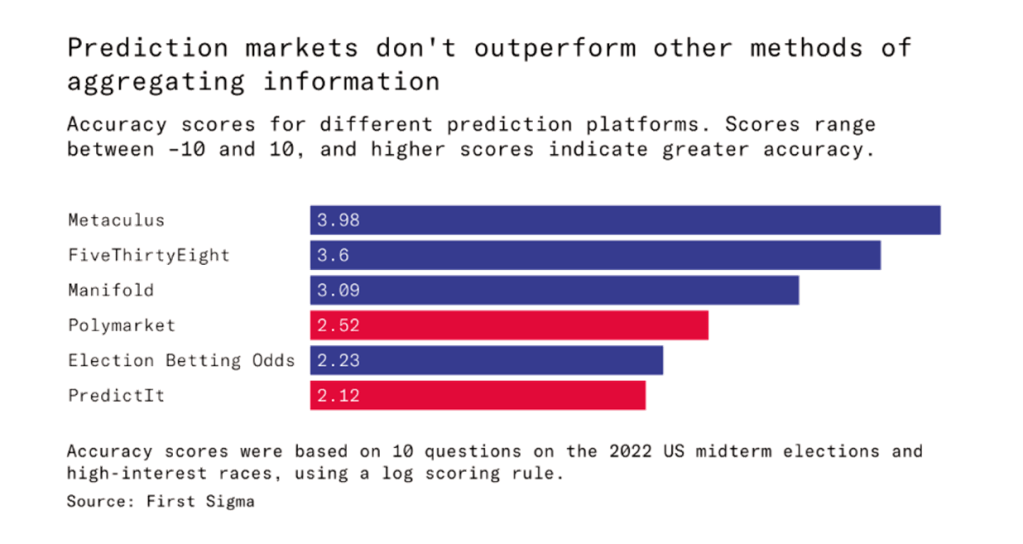

But the truth is that prediction markets have not yet acquired the relevance that many studies and authors have been anticipating for years. In particular in an area like scientific and technological prediction, where they would be revolutionary, they have not managed to overcome the simple Delphi method and the opportunism of consultants.

Why aren’t prediction markets popular, and in widespread use?

One usual (most common) explanation is regulation, but in a detailed review published in Work in Progress last May, Nick Whitaker & J. Zachary Mazlish put forward a different reason: Prediction markets are legal, contrary to popular belief. But they remain unpopular, because they lack key features that make markets attractive.

Rather than regulation, their explanation for the absence of widespread prediction markets is a straightforward demand-side story: there is little natural demand for prediction market contracts, They think that we can classify people who trade on markets into three groups, Savers, gamblers, and “Sharps,” but each is largely uninterested in prediction markets.

Our view is that prediction markets on everything – liquid markets over a wide range of important topics – will not work without subsidies. These subsidies would be expensive, so other forms of information aggregation are usually more attractive. The scarcity of prediction markets in the world today is not a failure of regulation, but a sign that they are much less promising than many advocates, including the authors of this piece, once hoped.

Prediction markets, unlike most asset markets, are zero-sum – in fact they are negative-sum, once you factor in platform fees.

As a consequence, the problem with prediction markets we have today is that they are small, with few traders and little professionalization…

However, there are likely benefits derived from having public, evident, aggregated forecasts. Politicians subsidize a lot of dubious projects, and if we are all interested in the future, for that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives, why shouldn’t we push prediction markets?

Wait. Maybe there is another possibility. Yes, the one you are thinking about while reading this post: Artificial Intelligence.

The Center for AI Safety has just announced FiveThirtyNine, Superhuman Automated Forecasting, a pun reference to Nate Silver’s 5382 & Philip Teclock‘s Superforecasting3

In a recent appearance on Conversations with Tyler, famed political forecaster Nate Silver expressed skepticism about AIs replacing human forecasters in the near future. When asked how long it might take for AIs to reach superhuman forecasting abilities, Silver replied: “15 or 20 [years].”

In light of this, we are excited to announce “FiveThirtyNine,” a superhuman AI forecasting bot. Our bot, built on GPT-4o, provides probabilities for any user-entered query, including “Will Trump win the 2024 presidential election?” and “Will China invade Taiwan by 2030?” Our bot performs better than experienced human forecasters and performs roughly the same as (and sometimes even better than) crowds of experienced forecasters; since crowds are for the most part superhuman, so is FiveThirtyNine.

Here is their technical note:

In this technical report, we describe a superhuman AI forecasting system. The system is designed to provide calibrated probabilities for a wide range of queries, from political events to global conflicts. Unlike traditional human forecasters or prediction markets, the forecasting AI rapidly aggregates and analyzes news and opinion sources, generating forecasts that are both faster and more cost-effective. Our evaluations on historical questions from the Metaculus forecasting platform demonstrate that the system matches the accuracy of expert human crowds. The demo is available at https://forecast.safe.ai.

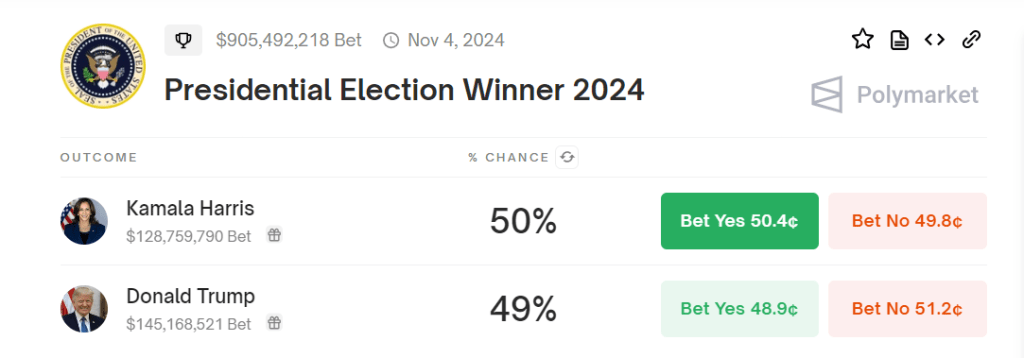

And here is an example (yes, THE question)4: Will Trump win the 2024 US presidential election?

Yeah, not far from Prediction Markets…

There is no reason why artificial and collective inteligence could not reach the same (inconclusive 😉 ) conclusion!

After all, for the time being, LLMs are just an instrument (enabling technology) of our collective intelligence. At least, until their become sentient and independent AGIs5…

____________________

(1) Neither this introduction, which I have repeated in several ocassions.

(2) Btw, Nate Silver has just published his own next smart move, not called 539

(3) Philip is also exploring LLM potential in forecasting

(4) Date: Sept 14. 2024. These images (probabilities) will change with time (and I guess they eventually disappear beyond the election day).

(5) For the time being, I am with Grady Booch. Here one of the simplest, clearer statetements on where we are today on our AI journey:

Featured Image: A robot betting on a prediction market, Replicate

[…] That relatively quiet phase is over. New platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi have popularized real money markets on elections, policy, macroeconomic indicators, and other sensitive events, with growing liquidity and media coverage. We have entered the familiar “tipping point” of adoption where the key questions are no longer “Do they work?” but “Who wins, who loses, and who controls the rules?” […]