Failure is critical for innovation to happen… Learning from failure, failing often, failing fast. Learning to fail is commandment #1 in the religion of innovation. And it’s ok. Innovation will always be risky and we do not have a better model. However, like in Campbell’s hero’s journey, it doesn’t mean failure is an easy burden for the hero —the innovator. (In fact, some cultures do not easily accept it).

Here is a brilliant story told in a paper published in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine by his hero, Jeffrey Flier.

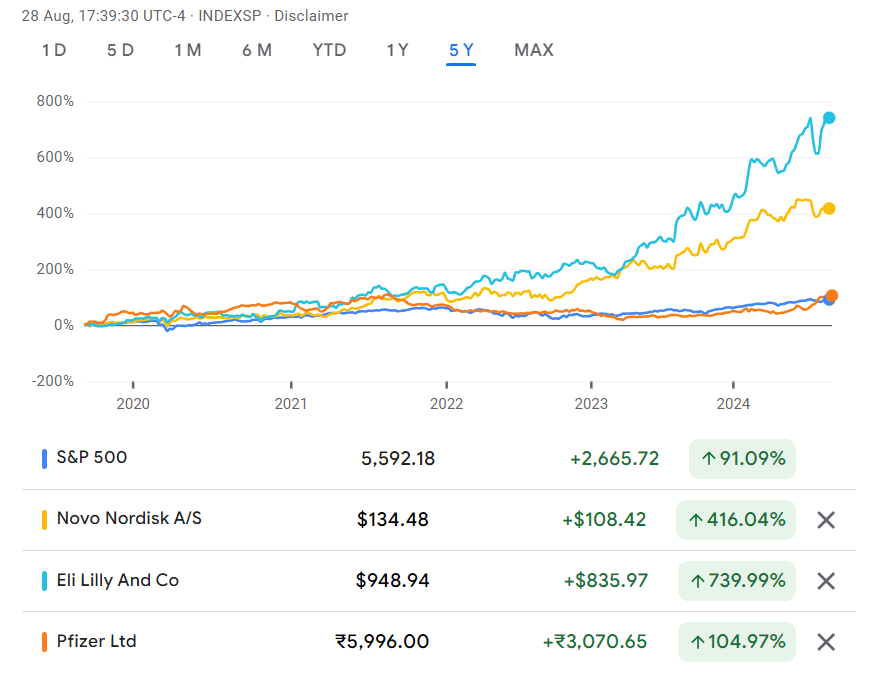

In 1987, he cofounded Metabolic Biosystems (MetaBio). The most important success of MetaBio was its demonstration of the anti-diabetic efficacy of GLP-1 in humans, a finding cut short by decisions of the startup and Pfizer, the major pharma company that obtained exclusive rights to the work and rapidly funded it.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a 30- or 31-amino-acid-long peptide hormone. Nearly 40 years later, the GLP-1 class of drugs for diabetes and obesity have emerged as clinical and financial blockbusters2.

MetaBio’s failure was not for lack of major progress in key areas of research. Working together with Pfizer, the joint team began to infuse GLP-1 into normal and then type 2 diabetes subjects. The decision to abandon the project is presented in the article as a perplexing judgment from senior Pfizer leadership who concluded “that there would never be another injectable therapy for diabetes other than insulin.”

How and why the early efforts of MetaBiio prematurely terminated should be of interest to historians, entrepreneurs, drug hunters, and clinicians3. And this is reason for Jeffrey Flier to publish the story1:

Many factors determine whether and when a class of therapeutic agents will be successfully developed and brought to market, and historians of science, entrepreneurs, drug developers, and clinicians should be interested in accounts of both successes and failures. Successes induce many participants and observers to document them, whereas failed efforts are often lost to history, in part because involved parties are typically unmotivated to document their failures. The GLP-1 class of drugs for diabetes and obesity have emerged over the past decade as clinical and financial blockbusters, perhaps soon becoming the highest single source of revenue for the pharmaceutical industry (Berk 2023). In that context, it is instructive to tell the story of the first commercial effort to develop this class of drugs for metabolic disease, and how, despite remarkable early success, the work was abandoned in 1990. Told by a key participant in the effort, this story documents history that would otherwise be lost and suggests a number of lessons about drug development that remain relevant today

The well-worn trope that “history is written by the winners” applies as much to the history of biotechnology companies as it does to the wars and other geopolitical events to which the phrase is more commonly applied.

In the 48 years since the biotech industry began with the launch of Genentech in 1976, followed soon thereafter by Biogen, Chiron, Amgen, and many others, much has been written to celebrate an industry that invigorated and reshaped the pharmaceutical business.

This is a story (history!) which I have personally had the pleasure to explain many times, and I have “less pleasurably” 😉 experienced first hand.

____________________

(1) Jeffrey Flier, ‘Drug Development Failure: How GLP-1 Development Was Abandoned in 1990’, Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, no. 1 (2024), https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/936036.

(2) The GLP-1 receptor agonists include semaglutide, which is marketed as Wegovy for obesity and Ozempic (Novo Nordisk) for diabetes, and tirzepatide, marketed as Mounjaro for diabetes and Zepbound for obesity (Eli Lilly).

(3) And for everyone actually interested in innovation. History repeats once and again, and in fact my own reason to publish this post is because this story clearly resembles other (today) well known stories about innovation.

Featured Image via Lexica Art