The greatest productivity revolution in human history began in the mid-19th century, when a few societies became the first to achieve sustainable rates of economic growth in the neighbourhood of 1.5% per year in real per capita income. The productivity revolution occurred within organizations, as atomistic individuals acting alone produce very little of an economy’s goods and services.

One classic explanation of the rise of organizations is that large managerial organizations were a response to technological change.

In a paper1 published in May, John Joseph Wallis argues that the key to productivity revolution is the adoption of impersonal rules for the first time in human history, rules that apply equally to all citizens and, effectively, “treat everyone the same.”

The central conceptual point of this paper is that if a society moves from identity rules to impersonal rules, then the society will find that all of the organizations that gain access to the impersonal rules that the government creates and agrees to enforce will become more productive. Exactly what those rules are about, for example, defining property rights, is of second order importance to the fact that the same impersonal external rules are available to everyone and that they apply equally to everyone.

The history of impersonal rules has hardly been written. The fact of impersonal rules is not in dispute, but the history of how societies came to adopt impersonal rules is very much an open question.

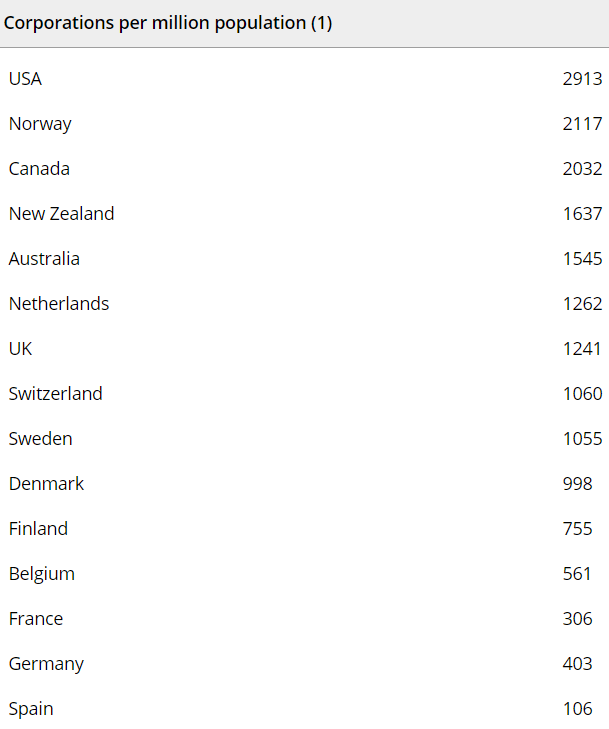

Next table lists the number of corporations per million population in the 1910 census of corporations compiled by Leslie Hannah. The countries listed had adopted impersonal rules for forming organizations, and they were the countries in which the productivity revolution of the late 19th century occurred. France, Belgium, and Germany are the borderline cases. (Next Spain 😉 )

Wallis’ argument is disturbing because the relationship it establishes between productivity and the elimination of identity. It is an idea recognized by all those who have argued in favour or against mechanization of society.

This is an insightful contribution, even though there’s a case to be made that more work needs to be done to establish the empirical plausibility of listing countries with impersonal rules by the early 20th century in the way that is suggested.

The paper is part of a special issue of The Manchester School which includes a selection of papers presented at the conference “Productivity revolutions: past and future.”

We may be living at the dawn of a productivity revolution era brought about by modern science and technological improvements… or not, because the truth is that productivity is the nearest thing we have today to Panoramix (Getafix) magic potion, and economists to haruspices.

____________________

(1) Wallis, John Joseph. ‘Rules, Organizations, and the Institutional Origins of the Great Productivity Revolution’. The Manchester School n/a, no. n/a. Accessed 14 July 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/manc.12483.

Featured Image: Peter Paul Rubens, The Interpretation of the Victim